The surprising history behind insulin’s absurd price (and some hopeful signs in the wild)

The price of insulin is iconic, doubling, tripling, multiplying like crazy, for a medicine Type 1 diabetics can’t live without.

To understand it, we went back almost 100 years and dug up a story of sweaty Canadian researchers, swatting away flies and doing business with probable dog-nappers, on the way to a Nobel Prize and a deal with corporate pharma.

Charles Best and Frederick Banting on the roof of the University of Toronto medical building, petting a dog they probably picked up from some shady character on the street and whom they would soon sacrifice in the name of science. (Photo courtesy University of Toronto.)

We also found hopeful signs out there today, including the folks at the Open Insulin Project in Oakland, California, who are working on their own recipe for insulin, which they hope to share as widely as possible.

If it sounds crazy, well, we talked with a listener who has hacked together an artificial pancreas from outdated equipment, raw computer parts, and open-source software, all with the help of her fellow “rogue, cowboy hackers,” who are growing in number. So, you never know.

Terri Lyman of Arizona shows off the home-made rig that regulates her blood-sugar and insulin levels according to her specifications. (Photo courtesy Terri Flynn.)

Meanwhile, activists with T1 International, an advocacy group run by Type 1 diabetics, are lobbying Congress, like the woman who leads off our story.

Adeline Umubyeyi, a T1 International activist, models a t-shirt from the group’s Washington, DC chapter president. (Photo courtesy Adeline Umubyeyi.)

They’re also organizing “caravans to Canada” (as our colleagues at Kaiser Health News recently documented with PBS News Hour)

You will find a TON of details, links, and resources in our newsletter. We’ve been told that even the sign-up process is pretty entertaining.

Dan: Adeline, um, went to bed without dinner a few weeks ago. It’s a thing she does sometimes, not because she can’t afford food. She can’t afford insulin. She’s a type one diabetic and if she skips dinner, she can skip a dose and be pretty sure she’ll live through the night

Adeline: so that way I can save enough until I get my next paycheck so that I can also afford my rent.

My car.

Dan: Note that Adeline’s 25, and she does not have to do this kind of thing as often as she did, like right after college when she was interning with a startup. Now she works at a law firm and it’s a good job with health insurance. There’s a deductible. So in June, she’s still paying for insulin herself about $350 every four weeks.

Adeline has known since she was a teenager that the price of insulin was gonna play a major role in her life. After her dad died,

Adeline: We didn’t really have health insurance, you know, so me and my mom would go to, you know, the CVS and they were like, you know, for her insulin, it’s gonna be $3,000. It was so heartbreaking.

I think that’s when I really realized, holy shit, like I’m on my own.

Dan: Like this wasn’t something her mom could really protect her from, not for the rest of her life. Her mom found the money. It was not easy. And from then on it was a scramble. Credit cards help from relatives, from non-profits, whatever it took.

And since Adeline’s been on her own, she’s always found a way, including skipping doses and skipping meals, which. Isn’t really safe. People die every year.

Adeline: You know, insulin for diabetics is like oxygen for us. We need it. If we don’t have it, we are not gonna be able to live until the next day. It’s really that simple, and that’s how I try to explain it to people.

Dan: And one out of every four type one diabetics rations their insulin. That is hundreds of thousands of people. Uh, this is old school technology. Insulin was discovered almost a hundred years ago by Canadian scientists who didn’t even want to patent it. They just wanted people to have it. That story is told in an amazing book called The Discovery of Insulin.

It’s got everything, especially scrappy. Naive researchers, swatting away flies in a sweltering attic, leaving a trail of dead dogs in their wake. And that story has a ton to tell us about how we got to this point. And where we might go from here may not be entirely hopeless. This is an arm and a leg. A show about the cost of health care.

I’m Dan Weissman.

Life before insulin was Stark. Here’s Jing Luo. He’s a doctor and a Harvard researcher who studies access to insulin

Jing Luo: through the 1920s, type one diabetes with a death sentence. Starvation in the midst of plenty. Um, kind of a rough way to die.

Dan: Yeah, unquenchable thirst, constant hunger and rapid wasting.

Frequent, uh, bonus symptoms include blindness, itching and boils. Boils all accompanied by nonstop peeing in Greek diabetes means pipe like liquid, goes in one end and out the other. An English surgeon in the 16 hundreds called it the pissing evil. And the urine is full of sugar.

Jing Luo: In addition to having profound thirst, drinking a lot of water, you’re peeing all the time.

Your urine was sweet,

Dan: so doctors confirmed your diagnosis with a taste test. Early 20th century Medicine had exactly one treatment for extending the lives of diabetics, slowly starving them to death. It was unbelievably grim.

Jing Luo: I find myself pausing and like wiping away tears, reading about, um, you know, for example, a small, nearly blind boy who’s wasting away and emaciated who they could not figure out, despite a very, very, very, very stringent starvation diet.

While he was still having glucose in his urine, and it turns out that he was eating the bird feed. From his pet, you know, that’s like crazy. Yeah. How can we do that to people? Yeah.

Dan: And that was a state-of-the-art treatment. Yeah.

Jing Luo: Yeah.

Dan: And starvation only worked for so long. Enter a struggling country, Dr.

Frederick Banting, seriously struggling. He hung out his shingle in July, 1920 and got no patience for weeks, months went by, he worried his fiance would break up with him. Then one night, Banting got an idea he hoped could give him his big break finding a treatment for diabetes, and he stayed up till 2:00 AM thinking about it.

At the time, scientists thought something in the pancreas might help diabetes, but something else in the pancreas, they thought interfered and banting had this complicated idea for isolating the good stuff. Take a bunch of dogs, make some of them diabetic by removing their. Pancreas then raid the pancreas of the other dogs using a dicey, untested surgical protocol that Banting has got in mind to isolate the good stuff.

They made a TV miniseries about the discovery of insulin in the 1980s. It shows Banting telling a friend about his idea,

Speaker 6: make an extract from this pancreas and pop that into the diabetic dog. Now, if the diabetic dog’s blood sugar goes down, I’ve got something.

Dan: A week after his sleepless night, Fred Banting was at the University of Toronto, pitching a big time professor of physiology.

He said, gimme a lab, a salary, and some dogs. The professor thought Banting was kind of a rube, and his idea was kind of half baked, but maybe not entirely worthless. So the professor said, no salary, but come back next summer. You can have some dogs and maybe a medical student to help. On May 17th, 1921, Banting and that student assistant cut open their first dog in the next two, three months.

They killed a bunch of dogs, some from diabetes, but mostly via incompetent veterinary surgery. The movie does a great job showing them, literally sweating it out. Fans going, no shirts, flies everywhere, and just fumbling. Here they are butchering another dog,

Speaker 6: Fred. I’m losing them. Got stretch on. Strap on.

Louis to shout For Christ’s sake,

Dan: no go dog dies. There’s a long, long pause. The assistant gets up, slowly, walks over, leans against a glass cabinet full of lab stuff.

Actor: I’ve never killed anything before.

Dan: So much for that cabinet. But for all that, they did produce some blood test results that showed promise hints that the stuff they were getting from dog pancreas might not be a total bust. So they got more dogs by hook or by crook going out and buying them on the street from, well, probably dog kidnappers.

And as summer ended. They managed to keep a diabetic dog alive for three weeks. Bam, game on. They got the university to buy them some more dogs, and in the next couple of months they learned they’d been taking the long way round. There was no need to get the pancreatic good stuff from surgically treated dogs.

You could just go to the stockyard, get some fresh cow, pancreas, or pig that could work too, and grind it up and go. Next, a more experienced guy joined the team, a biochemist named James Coop. Within a couple of months, coop had nailed down a method for making insulin. It’s a big moment and the miniseries really plays with that.

And then the really huge moment, the team tried this stuff out on a human subject, a 14-year-old kid who was down to skin and bones. It brought the kids’ blood sugar down to normal levels. They tried it on six more patients, good results. And so a few months later, less than a year after Fred Banting cut open his first dog.

They present at a big medical conference and everyone there completely loses their mind. By then, there were some problems for a couple of months that spring, they could not get a decent batch of insulin made. Coop. The biochemist was beside himself.

Speaker 6: You’d think recapturing It would be easy, especially for me.

I mean, I saw it. I held it in my hands.

Dan: And there were other problems too. Behind the scenes. Banting got convinced that the more experienced scientists on the team were trying to hog all the glory. He may have beaten up Colin, the biochemist, maybe twice. And meanwhile, there’s all these diabetics starving themselves to death.

And a US pharma company. Eli Lilly had been tracking the insulin research in Toronto for months. Sweet talking. The researchers had every opportunity, and the Toronto scientists had been putting Lilly off all this time. They did not want their discovery to become someone’s commercial enterprise, but they needed someone with resource.

Bigger labs, more capital to take insulin over the finish line. So reluctantly the researchers called Eli Lilly and said, let’s make a deal, and the rest you could say is grim corporate history. The deal that Toronto researchers made with Lilly was supposed to be limited, a way to get some insulin out there while Toronto figured out a way to get more insulin made for everybody.

Lilly got an exclusive license to make and sell insulin, but just in North America just for a year. But a year was enough to give Eli Lilly such a headstart. No US company could catch up and none did. The other two companies that sell insulin today are European, and they also got the basic signs directly from the Toronto researchers.

In that first year, Lilly made improvements to the insulin making process. Patentable improvements, trade secrets, and then over the next few decades. They went on to improve insulin itself. These early

Jing Luo: products are quite rudimentary because, you know, they were large amounts of volume of liquid. You’d have to inject into your, let’s say, the, the fat just, um, by your, by your belly button, um, or on your thighs.

And you’d have to do that multiple times a day. And, you know, because of impurities, you might have injection site reactions. Inflammation, uh, pain that might come from the fact that, um, who knows what’s in this ground up pancreas, you know,

Dan: modern insulin is a completely different thing.

Jing Luo: We’re not going to, to stockyards anymore, looking for animal pancreas.

These are all synthesized. Uh, these are more like designer insulins. They’ve been really, um, modified at a molecular level. It’s cool stuff. It’s super cool stuff. And, you know, there are, there are multiple Nobel prizes in physiology of medicine that have made this happen.

Dan: Uh, modern insulin is not new anymore.

Lilly’s product. Humalog came out in 1996. Some modern insulin isn’t even under patent protection, so why isn’t there generic insulin? Jing Luo says basically. There are easier things to knock off. Insulin is harder to make than regular meds like Tylenol, and it’s in a special class of drugs for which the FDA requires especially stringent and especially expensive testing.

And then there’s this, even though the active ingredient of brand name insulin may not have changed. There have been big changes and improvements to drug delivery systems like wearable insulin pumps. Patients like these pumps a lot better than shooting up with a syringe in the belly button, and the dosing is steadier, which means safer.

And there are a million patents involved in making insulin that works with those devices.

Jing Luo: Once you add all these different layers to this thing, to the medicine itself, companies can stack dozens of patents on top of each other to try to thwart generic competition because they can say, look, we’ve got three patents on the active ingredient.

We’ve got patents on the medical uses of the active ingredient. We’ve got patents on the non-active excipients associated with this ingredient. We’ve got multiple patents on the devices, and so you who are trying to enter this space, we’ll sue you for patent infringement on all of them.

Dan: Jing Luo says, this is standard with big pharma for pretty much everything.

Jing Luo: When you listen to these like CEOs of pharma companies being interviewed at CNBC, you know, they’ll be like, well, what about generic competition for this product? And they’ll just keep saying, no, no, no, no. We’ve got this really robust patent portfolio. We can withstand any challenge. We’re gonna tie this up in courts forever, and don’t worry about it.

We’re gonna continue this gravy boat for a long, long time. That’s the way they reinsure investors.

Dan: But the upshot is hundreds of thousands of people can’t afford the insulin they need to live. Which is why Jing Luo finds the book about insulin’s discovery. So moving,

Jing Luo: like what? We’ve come so far and yet we still have, um, adults dying, um, from rationing their insulin because of cost.

Yeah, it’s like. It’s, it’s, it’s so disheartening.

Dan: So this story started with a group of scrappy, kind of under-resourced researchers, and it turns out there is a group of exactly the same kind of people working on the problem of expensive insulin today in Oakland, California. That’s right after this break.

An Arm and a Leg is a co-production of Public Road Productions and Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit newsroom that covers healthcare in America. Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with the giant healthcare provider, Kaiser Permanente. We’ll have a little more on them at the end of this episode.

Hey. Also, I wanna tell you about a new podcast. It’s from Curved and it’s called Nice Try. The show explores the hidden stories behind how we design the world we live in, and what we learn when those designs fail. The first season is called Utopian and is hosted by Avery Truffleman. She is one of my personal favorite storytellers and she actually makes a cameo on this show in this episode about 45 seconds from right now in Nice try.

Avery investigates some of the world’s most fascinating communities, like an enclosed bubble of environmentalists and a 19th century religious sect that became a household brand. I just listened to that one. So crazy. So good. These are gripping forgotten stories on the very human urge to build the perfect place you can subscribe to.

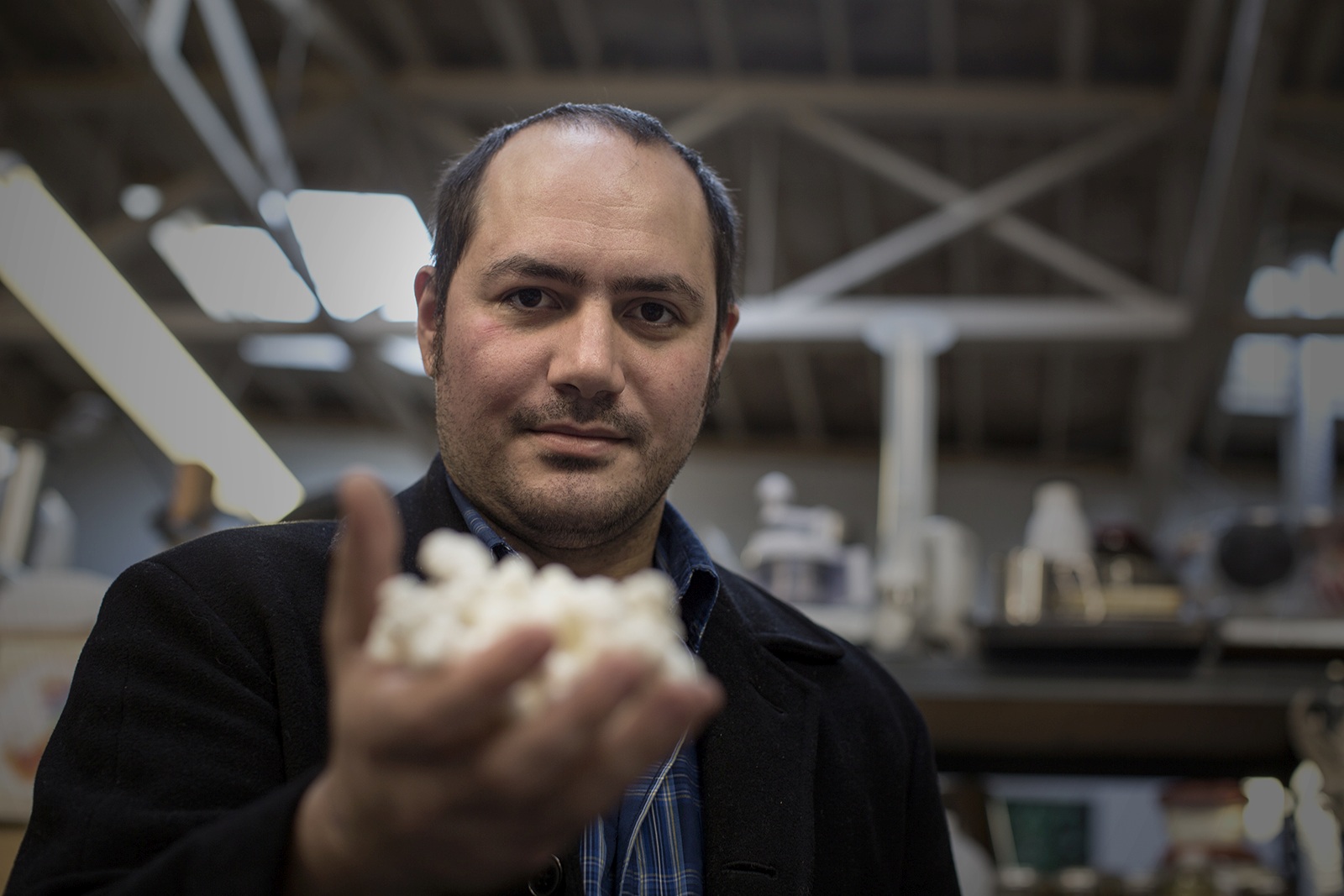

Nice. Try for free today on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get podcasts. Okay. Since 2015, volunteer researchers at the Open Insulin Project in Oakland have been working on a recipe for insulin with the goal of sharing that recipe as widely as possible. I mean, in an age where it’s possible to 3D print an actual house.

Yeah, really Google it. Why can’t we figure out how to make our own insulin? The project runs out of Counterculture Labs. That is a microbiology makerspace in what sounds like a kind of anarchist community center producer. Avery Truffleman lives and works nearby, and she very kindly went to check it out.

Avrery: Hi Dan. So I just biked up from my house to Telegraph Avenue, to Shaddock to Omni Commons, which is. A collective of collectives. It’s totally awesome. It’s like a very cool place. Um, and in the, it’s in this big beautiful building and they have a theater and, uh, food Not Bombs is here and a lot of other organizations.

And it’s Purdue Funny that this is the place where it all goes down.

Dan: Avery met the project’s founder, Anthony DiFranco.

Avrery: Hi, are you Anthony?

Yeah, I’m here. Hey Avery. Nice to meet you. Thank you for letting me come

Dan: crash. Welcome. Anthony is a type one diabetic. He is not trained as a biochemist. He’s a computer science guy, and he does enough consulting work with those skills to stay afloat, and he devotes the rest of his time to open insulin.

This is a lab with murals on the walls and a bike rack by the door. One of the other projects here is an effort to make decent vegan cheese and. Even the fancier lab equipment, like a super cold refrigerator has quirks.

Speaker 13: It’s kind of funny though ’cause it does look like a, a, a bridge at like, um, I don’t know, a house with a lot of people in it.

Like there’s lots of different like wishlists and handwriting and it’s very, it feels very homey. It doesn’t feel like a. I mean, it does feel like a science bridge, but it feels like a communal science bridge.

Anthony: Either you don’t kind of have to feel like you’re, you’re on a, a movie set that has the ideal of science.

You can do real science and just kind of do what you need to do.

Dan: And what Anthony wants to do in this funky little lab is to address the enormous problem of profit driven medicine starting with insulin.

Anthony: And I think there’s really broad acknowledgement that something really terrible is wrong with. The system, but we just have to like have the courage to name it and to propose alternatives later.

Dan: I get to ask Anthony some questions about their progress. He says, after four years, they’ve got a process that’s producing a little bit of insulin Next steps. Refine that process, publish it, and help other people learn to do it.

Anthony: It’s, you know, somewhere in the ballpark of what it takes to brew a really good beer.

So I don’t think it’s something that. Most people can’t do, but it does require you to put the time in and the attention in to get it right.

Dan: So this would be like a home brew beer kit for insulin?

Anthony: Yeah. I mean, it might be a little bit more like what you would find in a microbrewery than like a home brew kit.

Dan: He thinks a neighborhood operation maybe in a storefront or a clinic or even a pharmacy could serve a local community, kind of like a craft brewery. They’re starting to think about the practicalities. They’ve recruited some pro bono lawyers. They’re forming committees to write bylaws for a tax exempt nonprofit.

Jing Luo, the Harvard researcher would expect the craft brewery model to hit a regulatory brick wall.

Jing Luo: You can’t make enough of it in a sterile enough condition at. Capacity in order to get the FDA, who’s gonna inspect your plant to say, okay, I’m gonna approve you. This is not homeopathic treatments that you can just sell at the farmer’s market because of the DEA and the FDA.

Um, they would just shut you

Dan: down. Here’s a different perspective. John Picco is a professor at Colorado State who’s written about Oakland’s Open Insulin Project. He’s kind of a fan. They claim him as an ally. He’s also skeptical about getting FDA approval for open source craft brewed insulin, but he’s got his own idea bypassing the FDA.

Just like you don’t need the liquor commission’s, okay? To drink the beer you brew at home. You don’t need the FDA’s permission to make your own insulin.

John Pico: There is nothing that prevents a patient from manufacturing a drug for himself. You know, you can inject yourself with whatever you want.

Dan: What he imagines sounds even simpler, at least for the user than a home brew kit for beer.

John Pico: You know, the level of complexity is more like a bread machine too, for making insulin. I mean, that’s the level of complexity that we are talking about.

Dan: He tried raising money last year to get a project like that going, put out a YouTube video, but it didn’t take off. He only collected $197. Half of it.

From his teenage kids. He just gave you money from their allowance to do it. Yeah. Thought this was cool. Did you, did you give it back since you’re not going forward with it? Yeah. Okay, good. I asked Anthony DeFranco at the Open Insulin Project how he would deal with the FDA.

Anthony: Well, that’s, that’s, that’s a good question.

I mean, all of these questions of what this counts as in terms of regulation are. As far as I know, open questions and we’re eagerly awaiting the opinions from our legal counsel. I ask him how sure he is, they’ll get it

Dan: working and practical. Well, what’s the deadline? Uh, fair question. Meanwhile, diabetics die rationing their insulin every year.

And last year, Eli Lilly took in about $3 billion on insulin. So it sounds like the score is Eli Lilly, 3 billion scrappy researchers. Zero. So far as I was wrapping up season one of the show, I got an email with the subject line. I am part of a movement. It was from Terry Lyman. She’s a type one diabetic in Arizona.

She does not make her own insulin, but she has hacked together an artificial pancreas.

Terry Lyman: I can’t even begin to tell you how different life is with it than it was without it. I would never wanna be without it.

Dan: Her pancreas. It uses open source software that ties together an insulin pump and a glucose monitor.

Together they monitor her blood sugar and give her just the right amount of insulin to keep her at a healthy level. Her rig uses an out of date pump like from 2002 and a similarly old glucose monitor. That’s what’s hackable and a little thing she pulls out of what I think is an eyeglasses case. While we’re talking on FaceTime,

Terry Lyman: um, this rig is a computer.

That little thing there. This is the communication board.

Dan: It looks, this is like, this is like a raw motherboard from the inside. Yeah. This is what the inside of my computer looks like. If I took it apart.

Terry Lyman: Exactly. That’s the brain, that little silver thing. That’s the communications. That’s where all the antennas are.

’cause it’s got wifi.

Dan: Since she put her system together, the company Medtronic has come out with a machine that does similar things. Her doctor keeps asking her if she wouldn’t like to switch. She keeps telling him no.

Terry Lyman: So that new pump is hugely expensive and it doesn’t do half of what this does.

Dan: She has customized her system to give her more information hour by hour, day by day about how her body processes glucose and insulin and more control.

It took a lot of work.

Terry Lyman: I built my system over the course of a year. I was learning how to program computers. I mean, that process for me was long and slow. I’m 53. I am not a spring chicken, and learning to code is tough.

Dan: She succeeded because there were other people out there doing the same thing. A community a.

A movement,

Terry Lyman: even though it was hard, every time I had a question, every time I needed help, there was somebody online who could answer my question or could tell me where to read it. No, you’re on the wrong page. Go to this page. No, you don’t do it that way. You do it this way.

Dan: She shows me the real time readouts of her blood sugar, insulin levels, all kinds of things.

I tell her the whole thing seems pretty overwhelming

Terry Lyman: and yeah, it is a lot of commitment, but diabetes isn’t for the week.

Dan: The community around these tools is bigger than when she started. The tools are easier to use. She says The big medical companies haven’t taken legal action to stop them.

Terry Lyman: They, uh, called us names.

The big ones were rogue cowboy hackers. That was one slur. Which we were, we’re rogue cowboy hackers.

Dan: That is exactly what Anthony DiFranco wants to be for insulin. It’s what Fred Banting was. We need rogue cowboy hackers to combat or at least compliment the Eli Lilies of the world.

And there are other ways to be part of a movement. Remember Adeline from the beginning of our show, she has started volunteering with a group called T one International that advocates for Type one diabetics. Around the same time she talked with me, she told her story to more than a dozen members of Congress at an event in Washington C

Adeline: and I hope that I can help cause a spark and create a change.

Me

Dan: too. Next time on an arm and a leg, my medical device is spying on me for my insurance company so they can deny me coverage.

Speaker: And I was like, am I allowed to swear on this, uh, podcast? I was like, what? What the, are you talking about?

Dan: You can find links to a bunch of stuff about insulin prices on our website and even more in our newsletter, including.

Pictures from the Open Insulin Project and notes from a listener about what she does to make sure she’s got enough insulin and some other stuff. Just for fun. You can sign up at Arm and a leg show.com/newsletter. Hope to catch you there. Till then, take care of yourself. This episode was produced by me, Dan Weissman.

Our editor is Whitney Henry Lester. Our consulting managing producer is Daisy Rosario. Our music is by Dave Weiner and Blue dot sessions. Adam Raimundo is our audio wizard. Our intern is Daniel Fernandez. This season of an Arm and a leg is a co-production with Kaiser Health News. It’s a nonprofit news service about healthcare in America.

That’s an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News and the Foundation are not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente, the big healthcare provider. They share an ancestor. That’s it. It is a fun story. You can check it out at Arm and a leg show.com/kaiser. Diane Weber is National Editor for broadcast and Tanya English is senior editor for Broadcast Innovation at Kaiser Health News.

They are editorial liaisons to this show. Finally, thank you to some of our new backers on Patreon. I literally could not make this show without you. Pledge two bucks a month or more. You get a shout out right here. Thanks this week to Richard Meyer, Claudia and Larry Frame, Nikki Otten, Helen Laun, Lisa Bernstein, and Joyce Fox, David Chi Linsky, William Tanner, and David.

And No promises, but some people report a lot of satisfaction, a feeling of real accomplishment. When they pledge their support to an arm and a life like this guy.

Latest Episodes

Our favorite project of 2025 levels up — and you can help

Some more things that didn’t suck in 2025

How to pick health insurance — in the worst year ever

Looking for something specific?

More of our reporting

Starter Packs

Jumping off points: Our best episodes and our best answers to some big questions.

How to wipe out your medical bill with charity care

How do I shop for health insurance?

Help! I’m stuck with a gigantic medical bill.

The prescription drug playbook

Help! Insurance denied my claim.

See All Our Starter Packs

First Aid Kit

Our newsletter about surviving the health care system, financially.